Will Digital Fashion Weeks Replace Traditional Runway Shows?

/On March 26, Ida Peterson, buying director of London designer boutique Browns, should have been attending the first round of catwalk shows at Shanghai Fashion Week. Instead, with the help of a Chinese assistant on her buying team, she logged on to the Taobao app on her phone. Here, in a dedicated section on one of China’s biggest ecommerce sites, was a schedule for the Autumn/Winter 2020 season of Shanghai Fashion Week, which in the span of a month was transformed from eight days of shows and buying appointments into a fully virtual seven-day experience featuring shows from 151 brands.

Founded in 2004, the twice yearly Shanghai Fashion Week has become one of the pre-eminent fashion events outside of the Big Four fashion weeks in New York, London, Milan and Paris, thanks to the strength of the Chinese luxury consumer market and the growing recognition of Chinese designers at home and abroad. Participants run the gamut from local, high-end designer labels to international mass-market brands such as H&M and Gap.

But in early February, with the number of Covid-19 infections rising rapidly in China, it looked as if SFW would not go ahead. After announcing on February 10 that the March fashion week would be postponed, on February 28 organizers announced instead it would host a fully digital edition, to be live-streamed via the ecommerce app Tmall and its sister app Taobao.

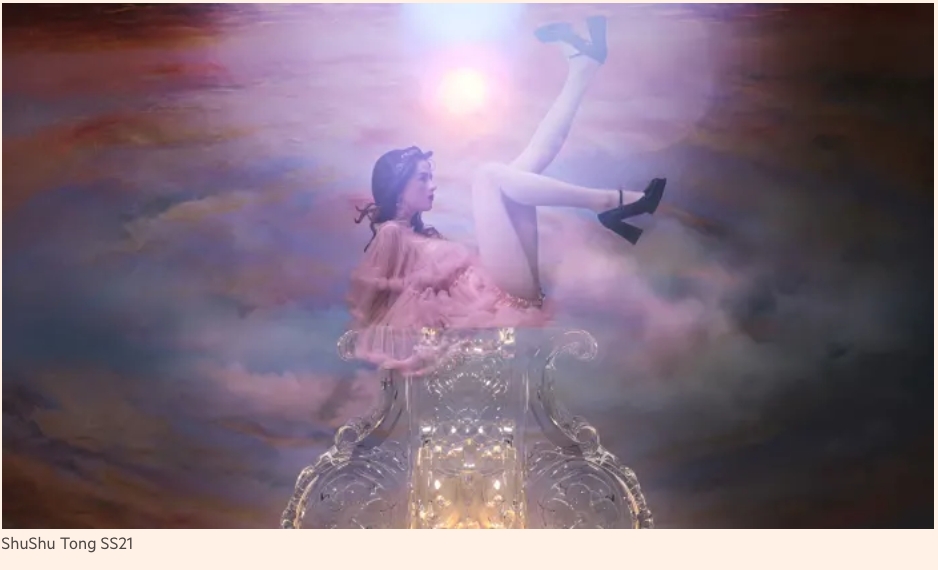

By then, the number of new Covid-19 cases in mainland China had begun to decelerate. After some resistance, designers moved quickly to prepare their show videos. Some were still scrambling to finish their collections after months of social distancing and supply-chain disruptions. “I had to cut all the fabrics by myself, [which] I haven’t done for a long time,” said the Shanghai-based designer Yutong Jiang of ShuShu Tong, who showed his AW2020 collection on the final day of SFW. “It [felt] a little bit like doing my graduation collection.”

SFW was organized like a typical fashion week, with designers allotted hourly slots to showcase their collections. But the similarities largely ended there. Some used their hour to host live-stream sessions, where they spoke to a general audience about their brands and showcased their Autumn/Winter collections or, in the style of a home-shopping network channel, hawked the spring collections that were already on sale. (As a non-Chinese speaker, I found these impossible to follow, but Queennie Yang, editorial director of the industry publication Business of Fashion China, praised live sessions such as Shuting Qiu’s, where the designer and her husband, who is the brand’s chief executive, spoke candidly about the history and purpose of their company.)

Other designers eschewed live sessions in favor of short pre-recorded videos that replicated the look and feel of a catwalk show, minus a live audience.

In ShuShu Tong’s video, a series of models styled as 1960s secretaries sat at typewriters, in girlish ruffled dresses or sweet gingham-print coats, fixing their make-up before picking up their top-handle bags and walking, one by one, through a revolving door. As a catwalk show, it was a perfectly good concept, but it was too repetitious to translate into an engaging video. More effective was designer Angel Chen’s five-minute show, in which fast-moving camera pans and a quick changeover of virtual, pseudo-apocalyptic sets — models walking through a gladiatorial ring at night, or past a cluster of stone head sculptures illuminated by lightning — made for a dynamic video experience.

According to Tmall, 2.5m viewers tuned in for the first three hours of shows, with brands such as Zuczug seeing sales conversions as high as 13 percent on their video streams. Larger commercial brands, who were able to drive their followers to their video feeds directly, accounted for the bulk of views; smaller designers said they reached audiences of 20,000 to 40,000. Yutong Jiang said he was pleased, as the audience for his live show is typically around 350 people.

Was the all-digital SFW a suitable replacement for real runway shows? For the industry members (designers, buyers, and editors) who tuned in, the answer was: not yet.

While an impressive first effort, SFW’s live streams were beset with technical glitches, and even the pre-recorded videos were too low-resolution to get a sense of the fabric and the quality of the construction.

Technology aside, there is the human factor to consider. Fashion weeks aren’t just about shows. Equally, if not more, important are the interactions that take place away from the catwalk: the meetings between designers and editors, where concepts and construction can be discussed in detail; and the private appointments between showrooms and store buyers, where orders are placed and young designers often discovered.

During SFW, Browns’ Peterson scheduled virtual appointments with Chinese showrooms but, without being physically present, she missed the opportunity to scour the rails in search of new talent, she said.

To be fair, the latest edition of SFW wasn’t designed with industry or international viewers in mind. Rather, it was reimagined as a public-facing event, meant to bolster brand awareness and drive purchases in China after weeks of store closures sent February sales of fashion and luxury goods plummeting by as much as 85 percent, according to Boston Consulting Group estimates.

Other fashion weeks are now following Shanghai’s lead and eschewing in-person shows for online events geared to engage the public and drive sales.

Moscow’s Fashion Week Russia, which runs from April 4-5, is streaming pre-recorded videos from about 30 brands (about half the number that typically show) on the e-commerce site Aizel.ru and the websites of magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar Russia and Vogue Italia. Designer participation is free — all costs are being covered by the Russian Fashion Council, its president, Alexander Shumsky, said.

In other parts of Europe, fashion weeks have been postponed or canceled.

Men’s fashion weeks in Paris, London and Milan, which were slated to take place in June, have been called off or postponed until September.

Both the British Fashion Council and Italy’s Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana are exploring digital alternatives to catwalk shows and showroom appointments.

These are all comparatively small fashion weeks. The bigger question is whether the next round of women’s shows in September will be able to resume as normal — which is looking increasingly unlikely.

What will be done if they can’t? Multibillion-pound brands such as Gucci and Burberry already reach millions with their shows and could redirect their budgets, and creativity, to more immersive digital experiences. It would be far more difficult for smaller designers, who lack the name recognition and finances to draw audiences and drive sales. At a minimum, they would need the support of local fashion councils to offer promotional and technical support. Buyers would need better, more interactive software to view collections, Browns’ Peterson says.

While Peterson doesn’t believe fashion weeks can ever be fully replicated online, she is enthusiastic about the improvements she is seeing in brands’ virtual showrooms since the outbreak of Covid-19, citing Burberry’s as among the best. She travels 10 months a year to see collections and would prefer to do more virtually if she could. “The carbon footprint we as an industry put on the world is pretty impractical,” she says. “[Because of Covid-19] we’re seeing some interesting innovations now coming through.”